Maine Master: Philip Barter

When the Bates College Museum of Art mounted a retrospective of Philip Barter’s work in 1992, the painter, then 53 years old, was on a major roll with regard to his reputation among aficionados of Maine art. His work was winging off the walls of prestigious galleries up and down the coast.

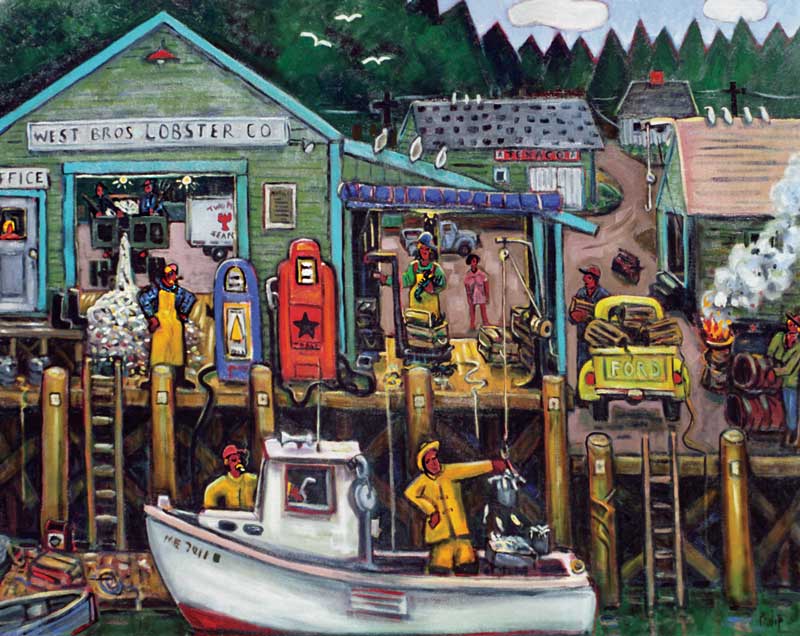

Barter was also in the middle of a major transition. Up until the late 1980s, his reputation as an artist had been tied to his narrative paintings: charming, boisterous, dynamic images of local life such as boatyards, local watering holes, firemen putting out a blaze. Unhappy at being labeled as a folk artist, Barter was moving toward more abstracted renderings of the Maine landscape.

Critics such as Maine Times writer Edgar Allen Beem and the Maine Sunday Telegram’s Philip Isaacson recognized the change. “[Barter’s] reduction of forms to suggestions of elements creates a new shorthand which plays against vibrant color,” wrote Isaacson, who noted that the resulting work, had “a feeling of rightness.” Both Beem and Isaacson pointed out Barter’s aesthetic kinship to the American modernists, in particular to his hero, Marsden Hartley, as well as to Arthur Dove and Georgia O’Keeffe.

Born in Boothbay and largely self-taught, Barter had decided early on that he wanted to emulate Hartley and become the “artist laureate” of Maine. To that end, he set out to paint the state, coast and mountains, lakes and streams, working from a home base in Franklin, northeast of Ellsworth. He learned how to simplify forms in a powerful manner that sometimes borders on pure abstraction.

Barter has always drawn from his downeast surroundings, giving certain subjects, like the vivid red of autumnal blueberry barrens, a recurring role. He has painted Schoodic Point and such local landmarks as Egypt Stream and the Carrying Place in every season and weather.

Farther afield, Barter has explored a range of motifs, among them, the Rangeley Lakes, the Portland skyline, the mills in Millinocket, and Ironbound Island in the middle of Frenchman Bay. The island’s dramatic cliffs, which attracted the likes of Childe Hassam, John Singer Sargent, and John Breck at the turn of the 19th century, thrust skyward in monolithic majesty in Barter’s renderings.

Working primarily from small simple sketches made on site, a practice he learned from sculptor Edwin Gamble, Barter takes license with his surroundings, heightening the color scheme and transforming the elements of the view into an arrangement of interlocking forms, both geometric and organic. He likes to remind viewers that the bright hues in his paintings are not far off from the real thing—just as his fellow downeast painter William Irvine has provided proof that the remarkable clouds in his landscapes actually can be found in the sky.

Barter turns to still lifes from time to time, bringing a similar eye for the unusual to his arrangements. “Still Life with Dan Falt Owl” features one of the Northeast Harbor sculptor Dan Falt’s wood creatures set in a decorative interior with woodstove and bowl. It’s a magical painting.

Born in 1939, Barter had an erratic art education, a mix of immersion in art history—van Gogh was an early god—and encouragement from older artists. The latter included Alfonso Sosa, an abstract expressionist Barter met while living the hippie life in California in the 1960s, and Frederick “Fritz” Rockwell, a painter and sculptor whom he palled around with when he returned to Boothbay in the late 1960s. They showed Barter the ropes and pressed him to keep painting.

While living out west, Barter had encountered the work of Hartley and experienced an aesthetic epiphany. He felt an immediate connection with the Lewiston-born painter. Hartley would serve as a kind of talisman, an artist to inspire but also to move beyond.

Barter faced challenges in the beginning. While he had some early success—he showed at Maine Coast Artists in Rockport and in several galleries—the painter could not make a living from his art. At the same time, he and his second wife Priscilla, whom he had married in 1973, were building a family, and he needed an income. So he dug clams and worms, was sternman on a lobsterboat, did carpentry, and pursued other work, all the while dreaming of the day he could paint full-time.

In 1984 Barter viewed “Waldo Peirce, 1884-1970: A Centenary Exhibition” at the Farnsworth Art Museum. Peirce’s lively scenes of Maine—county fairs, farmyards, swimming holes, and the like—struck a chord. Soon after, Barter was producing his own “story” paintings, entertaining and sometimes humorous scenes of downeast life. Six of these paintings were included in a traveling show, “Stories to Tell: The Narrative Impulse in Contemporary New England Folk Art,” organized by the DeCordova Museum in 1989.

The embodiment of self-reliance, Barter built a wondrous home and studio near the Sullivan/Franklin town line. Using found material, much of it gathered on the shores of the Schoodic Peninsula, he cobbled together a collection of cozy rooms to fit his growing clan. The wide-ranging décor, observed Bangor Daily News writer Jenna Russell, “creates the rough equivalent of a live-in sculpture.”

His family and home play an important role in his life. “My family is my nucleus of peace,” Barter told poet David Walker in 1990. In that same conversation, he discussed the influence of his faith. As a Jehovah’s Witness, he explained that he believed in “the creator and creation and that our obligation as humans is to do God’s work and be part of that in a peaceful way.” He also spoke of the balance he had found between his religion, his family, and his art, the latter being “part of the whole.”

Barter’s relief paintings highlight his ingenuity and his desire to avoid becoming stale. “I get too serious at the easel,” he told Aaron Porter of the Ellsworth American in a November 1998 interview at the time his wood relief mural was installed in the Sorrento Town Hall. For his view of Sorrento Harbor, which was commissioned through downeast culture maven Sturgis Haskins, Barter attached boats, docks, and trees to a backdrop of water, mountains, and sky.

Barter’s recent work testifies to the artist’s ongoing passion for design. A stunning relief painting of Sugarloaf featuring a pattern of zigzag ski trails recalls the winter abstractions of William Kienbusch. Another painting pays tribute to one of his friend Vic Levesque’s Nova Scotia draggers. Held together with cables, the boat bent up at the bow and stern. Barter painted it yellow because of its banana shape.

A new series of paintings, “Oasis,” offers variations on an image of a downeast blueberry field. This landscape represents a kind of refuge, a place of peace and safety in what Barter calls “these unprecedented times.” Upset by the current state of world affairs, the painter has turned to his faith—and to his art—for solace. In the process, he has once again led his viewers into a world apart yet recognizable, full of light and color.

Carl Little is the author of Philip Barter: Forever Maine, forthcoming from Marshall Wilkes.

Barter’s early images captured scenes of Mainers at work, such as this colorful and busy portrayal from the 1990s of Steuben’s working waterfront, titled West Brothers Lobster Co., oil on canvas, 36 x 48 inches. All photos of the artwork by Priscilla Barter

Barter’s early images captured scenes of Mainers at work, such as this colorful and busy portrayal from the 1990s of Steuben’s working waterfront, titled West Brothers Lobster Co., oil on canvas, 36 x 48 inches. All photos of the artwork by Priscilla Barter