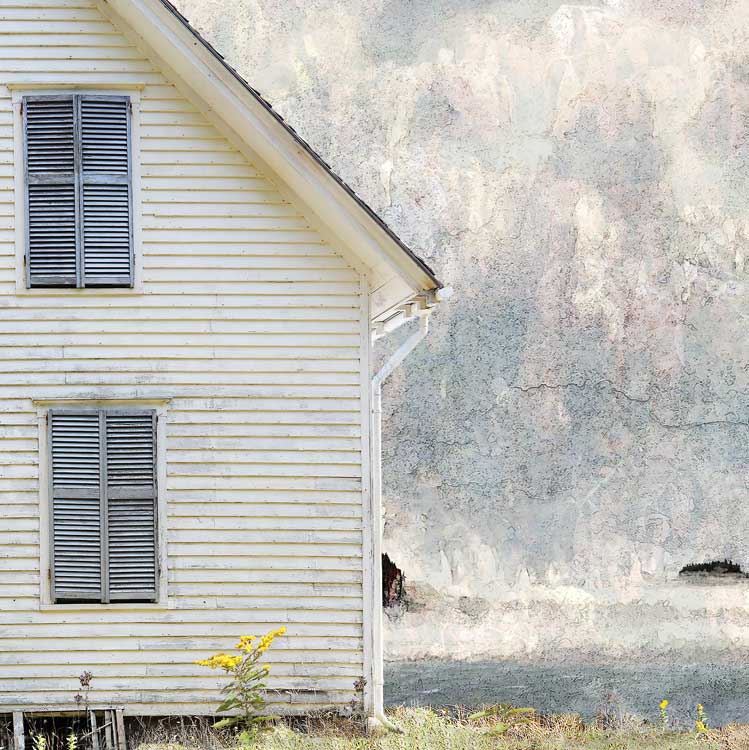

Jeffery Becton: Dream State

The work of Maine-based photographer Jeffery Becton melds interiors with shots of sea and sky, offering images that can come across as romantic reveries or manifestations of passing time. Using digital cameras, including the iPhone, Becton uploads images to Photoshop, where he crops, cuts and pastes pictures together. There’s a slightly Magritte-like mash-up in some, a hypnotic, Hopperesque vacancy in others. But when he discusses his work, he focuses on the emotional aspect of it rather than anything else. “Language is as problematic as thinking,” he says. “The eyes do a great job on their own coming up with meaning and feeling.”

An early participant in the digital revolution, Becton started out as a conventional portrait photographer after receiving a Master’s in graphic design at Yale. He began exploring Photoshop as soon as it appeared, and in the early ’90s, enrolled in a workshop at the Center For Creative Imaging in Camden, Maine, an initiative of the Eastman Kodak Company. “Moving from being a straight photographer to someone who altered the images to get something that felt right was a process,” he says. “I was very insecure about doing this. But at the Center—where they had the absolute best computers—I began to see that digital work is a legitimate kind of expression, its own medium.”

Many of Becton’s images have origins in the interiors of weatherbeaten summer cottages along the coast of Maine, to which he has unique access, given his family’s multigenerational history in the area. Often intimating decay and absence, life stilled or drifting away, his photographs possess a narrative attraction. And while he acknowledges that peeling wallpaper or a pair of old iron bedsteads can tell a story, he sees himself as much a formalist as fabulist. “That comes from my graphic design education, which was very Bauhaus and quite attentive to placement, size, texture—all the things that have to do with what makes a picture have an effect in the end.”

That something’s-not-right essence is often front and center in Becton’s pictures. Pink Door reads like a weather-beaten Maxfield Parrish crossed with a Cocteau film still. With Stage Door, it takes a moment to register the fog-shrouded sea just beyond. “Baker’s Bed,” he reveals, “came about because the large, multigenerational family that owned the house for so many years had to sell it and wanted a memorial. It’s a big summer house and over the years had seen whirlwind activity, growing as the children grew, until they spun off in many directions, leaving the vessel empty. I was simply trying to convey the joy and sadness that letting go involves.”

Becton’s process is more a visceral than an intellectual operation, one that begins with an image that excites his own eyes. “I need to be enthusiastic about what’s in front of me, a formal structural kernel that suggests other things,” he says. “I try to see what can grow organically from there. Sometimes it’s a long slog. Sometimes I give up, but not very often. I’m very tenacious about finding what works.”