Artist Alison Rector

“While many Maine painters are known for their depictions of the state’s iconic landscape, artist Alison Rector has gained acclaim for her interior views— light- filled spaces, both public and private.

Prior to moving to Maine in 1990, Rector had painted portraits and self-portraits. Once settled in her new home here, she responded to her surroundings, painting gravel pits and trailer homes. She turned to interiors after she began studying with Belfast-based artist Linden Frederick. Rector first heard Linden talk about color theory at Artfellows, an artists’ co-op, and was intrigued. A few years later she took a one-day color theory class with him at the Farnsworth Art Museum and subsequently arranged a private tutorial, visiting his studio to learn more about oil painting technique. is was, she said, her graduate school.

Rector had been trying to understand color and light, but the constant shifting of both in the landscape made it difficult. Inside, she found she could control the light source.

When she began showing her paintings of interiors, people reacted favorably, attracted by the psychological content. They also liked her alternative approach to the ubiquitous image of a Maine landscape, although many of Rector’s canvases incorporate landscapes, as seen through a doorway or window.

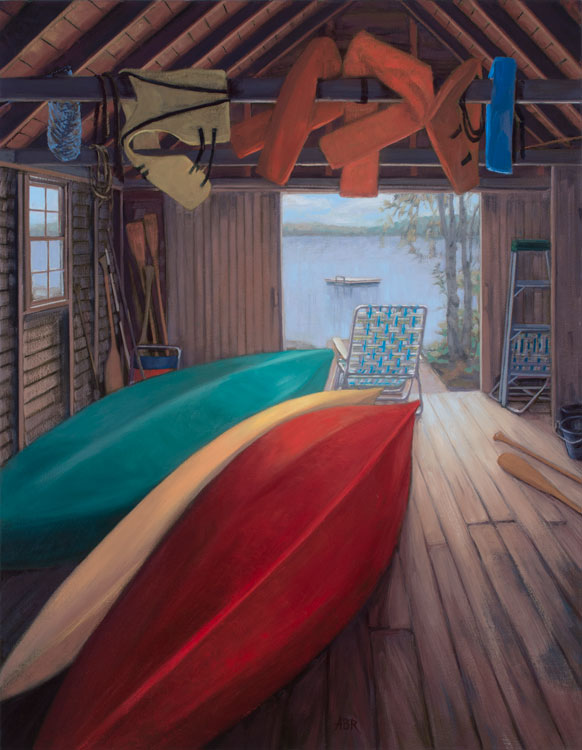

The interior became Rector’s trademark subject. She was drawn to particular places, including older Maine houses and camps with simple décor. While she rarely includes figures in her paintings, often the furnishings evoke the presence of people. The life preservers hung in the rafters in Boathouse Reverie, for example, stand in for swimmers in this rendering of a camp in Stoneham, Maine. Rector rearranges elements of a scene to enhance the engagement with the viewer. Here, three nesting kayaks with colorful hulls lead the eye past a lawn chair to the lake beyond and a boat waiting on the water.

Another evocation of a summer retreat, The Radiant Island, exemplifies Rector’s mastery of light. In this image of the community building, called the Casino, on Little Diamond Island in Casco Bay, sunlight casts shadows across the room, empty but for a ping-pong table in the center. The painting has an ethereal quality.

“Light is really what interests me,” said Rector, adding, “I still marvel that painters can take a basically plastic opaque material and create a feeling of light.” With each canvas she strives to reach that moment when “patches and bits of paint” coalesce and she says to herself, “Yeah, that’s the thing that got me when I saw it.”

Rector is perhaps best known for her series of library interiors, now numbering 45; she showed a group of them in “The Value of Thought,” a solo exhibition at the Ogunquit Museum of American Art in 2017. Initially inspired by a visit to the Blue Hill Library in 2010, the painter set out to visit and paint all 18 Carnegie libraries in Maine and ended up painting many more along the way.

While some of these structures have undergone renovations to keep up with the changing needs of the public, Rector focused on “the original bones” of the buildings, scouting each one for quiet spots where the light was less fluorescent and the architectural elements—recessed alcoves, window shapes— were interesting. She also painted a number of libraries from the outside.

Rector views libraries as places of knowledge as well as sanctuaries. She has expressed concern about what she views as a popular disregard for the value of intellectual study and thought. “Would that our current leaders would say they care about the complexity of intellectual discussion,” she said.

Rector recently embarked on a new series related to railroads. “I’m kind of moving on from libraries now,” she said. In her studio are paintings of a railway bridge in Belfast and another of the train platform at Union Station in Springfield, Massachusetts, viewed during an Amtrak trip from South Station to Rochester last summer (she worked from sketches and photographs).

The latter painting reflects Rector’s interest in “the hidden views” of New England’s industrial past. “The train came through for me,” she reported, “providing views of the back sides of old warehouses, neglected back lots, suburban backyards and urban centers.” She will premier these paintings next August at Greenhut Galleries in Portland in a show called “Train Journey.”

Rector was born Alison Berard in Rochester, New York, in 1960, and grew up in Bethesda, Maryland, in the D.C. suburbs. Her father had been finishing up a medical residency in Rochester when he was offered a position as a cancer researcher for the National Institutes of Health.

After graduating from high school in 1978, Rector attended Brown University. A major draw was being able to take classes at the Rhode Island School of Design. She enjoyed interacting with the art students, but first and foremost she wanted to get a liberal arts education, a decision she has never regretted. “I really learned reading and writing and critical thinking,” she said.

After college, Rector lived briefly in Boston before moving to San Francisco. During her four-year “adventure” on the West Coast, she made a living in the food industry, baking and cooking. She worked for food icon Alice Waters in her Café Fanny in Berkeley. The experience was life-changing—and inspired her eventual move to Maine.

Alison and her husband, Eric, met in a restaurant. They both love good food and their desire to be able to grow some of their own, inspired by Waters’s maxim that you’ll never get a better tomato than one that goes straight from garden to plate, sent them north from Boston in 1990. They purchased a farm in Monroe and embraced the homesteading life, raising sheep, cows and chickens and making apple cider. “We did a little of everything in a back- to-the-lander kind of way,” Rector recalled.

About eight years ago, when she turned 50, Rector started thinking about where she wanted to be later in life. She and Eric loved living on the farm, but they weren’t sure they wanted to be rolling hay bales and cutting firewood for the rest of their lives. Working through the Maine Farmland Trust’s Farmlink program, they contracted with some young farmers to incrementally purchase the property while running the farm. “It’s like a dating service,” Rector explained: “you look at each other’s profiles and if you find a match, you work out the terms of your agreement.

The couple built a home on a hill overlooking the farm. Their “passive dacha” is a super energy-efficient house, insulated so that the inside never goes below freezing. They also own a small condo in South Portland, which is their true plan for later in life. “I’d love to be able to walk to the library and grocery store,” Rector said.

When she isn’t painting or taste-testing one of her husband’s artisanal cheeses—Eric runs Monroe Cheese Studio in the barn next door—Rector helps out at several nonprofits, including the Funeral Consumers Alliance of Maine. When her parents died a decade ago, this organization helped her and her sister navigate the process. She recently represented the alliance on a segment about green burials on Maine Public Radio’s public affairs program “Maine Calling.”

In a presentation about her work at the Courthouse Gallery in Ellsworth a few years ago, Rector mentioned experiencing a “hiccup” when her parents died. She had a spell of self-doubt. But life is “constantly evolving and you can come back to important things,” she said. She admits to having moments when she thinks to herself, “Okay, I’ve said everything I’m going to say, I guess that’s it,” and then she gets excited about something new, like the views from a passing train. Soon she returns to her studio in the woods and starts to lay out a new painting.

(To read this article in Maine Boats, Homes & Harbors and see the mentioned paintings click on the link: https://maineboats.com/print/issue-157/artist-alison-rector)

Carl Little’s recent books include Philip Frey: Here and Now and Paintings of Portland, which he co-authored with his brother David Little.

Alison Rector’s Boathouse Reverie, 2017, evokes a summer day at a camp on a lake in western Maine. Oil on linen, 28″x38″

Alison Rector’s Boathouse Reverie, 2017, evokes a summer day at a camp on a lake in western Maine. Oil on linen, 28″x38″